Interview with John Skube

2012 October 22

Yakima, WA

By Barbara McMichael

BM: My name is Barbara McMichael, with the Highline Historical Society. I am here today in Yakima, Washington, on October 22, 2012, to interview John Skube, who was a long time resident of the Highline area.

Mr. Skube, if you could tell me briefly about your parents. Who they were and where they came from.

JS: My dad [John, Sr.] came from Vienna.

BM: Why did he come to this area? The Highline area.

JS: He met my mother. His family lived on Madison Street in Madison Park. He wanted to be more out in the country. So they bought some acreage out in Southern Heights.

BM: I did skip ahead, I apologize. Your mother’s name was Josephine and she was born back in the Midwest, right?

JS: In St. Paul.

BM: Why did she come out to Seattle?

JS: Her father got killed on the railroad. Her mother’s brother had a big logging operation in the Duvall area. He sent for them to come out, she and her younger brother. They grew up in the Duvall area. Then she and her mother and brother moved to Seattle so they could go to school.

BM: So then your dad came out from Vienna —

JS: From Vienna, he went to Duluth. That was the steel industry. They followed the steel industry. Then they came to Seattle and he met my mother. My dad had some sisters that were in the choir at the Immaculate Conception Church in Seattle. They introduced my dad to my mother.

BM: So, they made beautiful music together.

JS: Yes, they did.

BM: Tell me when they got married. What year did they get married?

JS: It was four years before I was born so it had to be 1914.

BM: You were the firstborn child, so let’s talk about that. Your birthday was when?

JS: December 29, 1918.

BM: Okay. Then you ended up having some sisters and a brother who came after you isn’t that right?

JS: Yes. I’m the oldest of the four.

BM: Tell me about your childhood in Southern Heights.

JS: Of course, I was quite young. I remember some of the surroundings. It was in the country then. There were orchards there and that sort of thing. My parents sold that place and we lived temporarily on 4th and Lucille in the Georgetown area. We rented. From there we moved to Aline Heights.

BM: Where is that?

JS: That’s not far from South Park, but closer to the city.

BM: Closer to Seattle?

JS: It’s off of the Des Moines Highway on a hill where we could see the city of Seattle.

BM: I see, okay. When you saw the city of Seattle what were the major landmarks? What could you see at that point?

JS: Well, the tallest building was the Smith Tower and the biggest building was Sears Roebuck at First and Lander.

Basically, I grew up there and went to St. George’s Grade School in Georgetown. From there to Cleveland High School, which is in Georgetown, also. Then another kid and I hopped a freight train and we wound up in Texas and Colorado.

BM: How old were you?

JS: Sixteen.

Cleveland was a city school and Highline was a county school. The city schools started about two weeks before the county schools. So my mother got me enrolled in Highline. We lived right on the borderline. So then I graduated from Highline.

BM: So after you got back late from Texas you ended up going to Highline?

JS: Yes. You know, we rode around the country a little bit.

BM: What an adventure. So that would have been —

JS: That was depression time and the railroad used to put on extra cars for Okies and people that were coming from the Midwest. Most of the time we rode on top of the boxcar. There was a sidewalk like on top of the boxcar and you just lay up there and hang on.

BM: Tell me a little bit about that experience. How did you eat? What did you get to eat? What kind of people did you meet?

JS: Some flat cars had like 50 or 60 people on them with their children. They were having a hard time in the Midwest, the dust bowl and all that kind of stuff.

The thing I really remember is laying on top of the boxcars and hanging on. There is a wooden sidewalk and you’d raise your head up and look at the boxcars going like this [waving hands] ahead of you.

BM: What about when you went through some of those tunnels in the mountains? That must have been terrifying.

JS: Well, you had to hold your nose.

BM: I imagine the smoke must have been terrible.

JS: Yes.

BM: Did you have anything to eat on that journey? Did you hop off the train?

JS: There were a lot of towns you were told you better get off, that they didn’t want hoboes. We weren’t hoboes, just kids having an adventure. But you didn’t want to get inside of the limits because, what they used to call the railroad bulls would run you out of town. So we managed to do things. I dug potatoes and picked some hops and different things.

BM: What a great adventure. How long were you gone? Was this a few months?

JS: Yes, a couple months.

BM: So, when you came back to Highline, tell me about going to school at Highline High School.

JS: Well, Highline was a completely different school. Different type of kids, more country.

BM: Different from Cleveland where you’d been to the city school.

JS: I loved Highline.

BM: Tell me about people you remember, kids, teachers.

JS: One thing I really remember, I just got through with. I met a girl. Well I went to St. George’s parochial school. We didn’t have any Japanese kids. When I got to Cleveland in my sophomore year I was in class with a Japanese girl named Toshiko. How this interview and everything came about was my daughter, Jane, was home and looked at my old Cleveland annual and saw the beautiful note this Toshiko wrote and the beautiful penmanship. So she pursued that and she found Toshiko. Of course, Toshiko being Japanese was rounded up and put in different locations around the country.

BM: Sure, during World War II.

JS: Anyway the upshot of that was I did talk to Toshiko just a few weeks ago.

BM: After all these years.

JS: Our teacher was Johnny Cherberg. That was his first year of teaching.

BM: This was back at Cleveland still.

JS: Yes, at Cleveland.

BM: Because we’re the Highline Historical Society, we’re interested in those Highline memories, too. Do you remember a special class or special activities you did when you were at Highline High School?

JS: Well, going back to Cleveland, I was on the golf team. I actually didn’t participate too much in sports at Highline. I was involved somewhat but didn’t actually play. But I had a lot of very good friends there. I took shop and architectural drawing. It was just a great school to be in. Had a lot of good friends.

BM: What sorts of things did you do outside of school with your friends. How did you entertain yourselves? Or were you all working in your high school days? Did you go off and play golf with people?

JS: Yes. Played quite a bit of golf.

BM: Where did you play?

JS: Different courses around – Foster, Lake Tapps, Lakewood, which was up by White Center. Played there mostly. I had a car.

BM: Oh, what kind of car did you have?

JS: Model T. I don’t know, just what a kid does in high school.

BM: Sure, but what you did in high school was different from what kids are doing now, which is why we’re trying to capture that.

Tell me about this Model T. Where did you gas up? What gas station did you use?

JS: Well, you know you could buy gasoline at times for 10 cents a gallon. With the old Model T, my friends and I, we’d go to a gas station and get some used oil and mix it to stretch it. The car smoked a little bit but it would give us more mileage.

BM: Tell me a little bit about Des Moines Memorial Way. I think you have some stories about that road. What do you remember about that stretch of road?

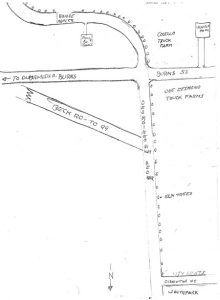

JS: Well, get that little cartoon I drew you.

BM: Yes, which you have right over there. Isn’t that it?

[Following are comments indicating locations along Des Moines Highway on a map John drew. See page 11.]

JS: Okay. Well when you look at this, this is the Des Moines Highway, and this is the city limits. This is Director Street. This here is South Park. Going this way would probably be west and this is the brick highway. These are the elm trees This heads on out and ends up at Des Moines. It was red brick. The story was that it was built by the King County prisoners.

BM: Did you see them building it or was that before your time?

JS: Yes, it was before. Then this is Joe Desimone. Joseppi Desimone.

BM: Sure, the truck farms.

JS: He’s the one that founded the Pike Place Market.

BM: Right.

JS: This is the Colello family. They had a garden. These were all truck gardens. Joe hired a lot of Filipino people and a lot of Japanese people. This is Burns Street here. This is Seattle Packing Company. That was a slaughter house.

BM: What kind of animals would get taken in there?

JS: Steers, cows, pigs.

BM: Did people have their own animals that they would take in to have slaughtered there?

JS: No, they brought them in and they had corrals here.

BM: Must have been a terrible smell around there.

JS: I worked there when I was a little bit older. I’d work at night and I’d work on Saturday. Washed the trucks and so on.

Then this Des Moines Highway continues on. This is Hamm’s Creek, this is the bridge over it. The Hamm’s owned a lot of land around here. Mrs. Hamm built a beautiful big building there that was a gentleman’s club when she built it. People came out from Seattle to stay over the weekends and so on. But when we were kids it was sold and was the Danish Old Folks Home. Then this continued on out past the Rainier Golf Club and through Sunnydale and on out to Des Moines. Which in those days was a long ways out. Then this road turns off and was called the Beck Road. It is now a freeway that goes right straight through over toward West Seattle. Every Memorial Day some group put flags on each one of these Elm trees.

BM: Were the trees full size at that point?

JS: They were, I would guess, about between six and eight feet tall.

BM: Really, that young still.

JS: An interesting thing about the Des Moines Highway, it was red brick and in the summer when it got real hot, sections of it would explode. Each brick grew from the heat and of course, it could only go up. I did witness a couple of explosions. Bricks 50 feet in the air and falling all over.

BM: Did people get hurt from that?

JS: Not that I ever heard. When it did that, later on, after the old road was built, they patched it with asphalt. So if you looked at the old Des Moines Highway, it had a lot of patches in it.

The Hamm’s bridge is over the Hamm’s Creek. She [Mrs. Hamm] has a creek named after her that comes down through a canyon.

BM: Tell me a little bit about Mrs. Hamm. What do you remember about her?

JS: I don’t think I ever really spoke to her very much, just outside of “Hello.” I never met a Mr. Hamm. In later years I got to know her son, Charles. He went out and started a pharmacy in Seahurst. You probably know where that is, the west end of Lake Burien.

This Burns Street, it ran over toward West Seattle and then it ended at the Duwamish River.

BM: There was a drive-in down at the Duwamish River. Did you ever go to that, the drive-in movie theater down there?

JS: Yes, there was one out along the Beck road.

BM: I don’t remember that. I remembered it coming down along Highway 99, came down the hill and so on.

JS: The Beck Road, it ran into 99, quite a ways out. Of course 99 was the main road to Tacoma and on through to Portland.

BM: Once you graduated from high school, then what kind of work did you pursue?

JS: I did a lot of little jobs. I worked at the Seattle Pack, some. Then I wound cable, IBM. I worked on airplanes.

BM: Was that for Boeing?

JS: Oh, no. Just for Northwest Propeller and a few places. They were mostly wooden propellers. I scraped them and varnished them.

BM: Was that down at Boeing field?

JS: Yes, Boeing Field.

BM: Ok. Tell me about Sea Tac Airport. Was that part of your experience at all?

JS: Well, when I was a kid, the runway ran about a 45 degree angle to what it does now.

BM: Really?

JS: Then when they put in the new runways, they ran parallel with Interurban Avenue, which runs into Georgetown. There was just a few little hangars.

BM: Now, you’re talking about Boeing Field?

JS: Yes. We saw when they built the administration building, saw it go up.

BM: Now, before that time, I think there was a race track down there.

JS: Yes there was. That was down by what they call Oxbow. There was a race track and some sort an old folks place or something. There were little towns there – Duwamish, Allentown, and so on.

BM: Each one kind of separate and distinct from one another.

I’m trying to get to the point where you ended up working for a steel company. But I don’t know how you became involved in working for that.

JS: Well, how that started was my grandfather was a patternmaker. My father was a patternmaker. They wanted me to carry on the tradition. I had gone and put an application in at the Boeing plant, which is what they call the Old Red Barn now. There were two men you had to see. Weaver and Carr. They were the personnel directors, I guess. Anyway, they didn’t call me. But at the same time I put my application in at Pacific Car and Foundry. I got a call from them that the apprentice was just about out of his time and that I could start being an apprentice. That was a five year apprenticeship. However, at that time the war was heating up in Europe. So I went to work at Pacific Car in September 1939. I was only there about a year. What they call the corporation shop employees, the patternmakers, went on strike. So there I was, I didn’t have enough experience to go to what they call a jobbing shop.

I had met a guy and he told me Great Northern was looking for a go-fer in Essex, Montana. So I went to the Great Northern Railroad office and applied, told them my situation. I ended up working in Essex, Montana in the Isaac Walton Hotel. That’s on the border of Glacier National Park. They furnished me with a ’36 Studebaker and I’d run down to Kalispell or over to Browning and pick up what they had ordered, because this Isaac Walton Hotel was a hotel for railroad employees. There was like a roundhouse close by. When the freight trains were heading east they stopped there and put in an extra locomotive to get them over the summit, which was right up at Glacier Park.

I was lucky because I got to know all the engineers and everything. I had the opportunity at 11 o’clock at night when the big freight came through, I could ride up to the summit in what they call mallets. Huge, huge steamers. We’d get up there and, of course, it was always pitch black. I never did know how they turned that around, but the fireman, there was just two men in the cabin of this thing. One got off with the lantern and they went forwards and backwards, and clanked around. Pretty soon we were headed back down the hill. That particular run had the highest trestles and the longest snow sheds. That was the tail end of the steam generation.

BM: How long did you do that?

JS: Just a few months. Then the strike ended and I came back.

BM: What a great adventure to have in the meantime. So then you came back to —

JS: Pacific Car and Foundry, it was then. It didn’t become PACCAR until they got big enough to get on the stock exchange. So they changed the name to PACCAR.

BM: Tell me a little bit about the work you did learning how to become a patternmaker. What is the work involved?

JS: It’s a highly skilled trade. It’s very complicated.

BM: For somebody who doesn’t know anything about working in a steel mill, what did you do precisely? Did you design the shape of beams? What does a patternmaker do?

JS: We built our patterns out of wood. We used good Honduras mahogany. It had to be wood that was stable. We were basically making winches, hoist cases. You had to make the inside and outside. It’s very complicated. You had what you call patterns, and core boxes. Then they’d take them into the foundry. They put them in what they call a flask. They were covered with sand. It’s not your beach sand, it’s a treated sand that holds its shape. Then they remove the patterns and put the flask back together and pour steel in them.

BM: So, as World War II was continuing, a lot of fellows were going off to war. But, you did not go off to war. Can you tell us why?

JS: There was a vital shortage of patternmakers because of the five year apprenticeship. I started out for 25 cents an hour. Most kids couldn’t wait that long. They’d go to Boeing and get 5 or 6 dollars an hour. You had to be dedicated to do it.

Anyway, the government came along and built Pacific Car and Foundry as a state of the art foundry. Being as I was kind of the junior member, I wound up, before I completed my apprenticeship, doing the pattern shop at night because they had to have somebody there in case a pattern got broke or something. Eventually I got my certificate. After that I had a couple of inventions, and they put me in management. I didn’t actually invent something, but I invented the procedure for manufacturing it that saved the company a lot of money. So they put me in management. Then besides running the pattern shop, I did foundry engineering, figured casting weights and all that sort of thing. How to feed the castings.

BM: You spent your whole career doing that, isn’t that true?

JS: I stayed there for 36 years.

BM: Let’s back up a little bit because somewhere along the way, you met a charming lady who became your wife. Can you tell me a little bit about your courtship and how you met the lady who became your wife?

JS: Prior to the time the government built us a foundry, we just had first aid. We had an old Ford ambulance. If somebody got hurt they’d take them over to the doctor’s office in Renton. But when the government took it over they said we had to have an RN. My wife was just out of school and she became the RN. I had a lot of competition – about 3000 guys, you know. [laughing] Of course, I thought she was the most beautiful thing I ever saw, in her uniform and everything.

BM: So what did you do to win her heart?

JS: Well that took a while. We courted for a over a year. She had to keep working to make money to pay her dad’s phone bill and sort of things like that. Then we had a little, didn’t amount to much, but a religious problem. We solved that.

BM: You were from different faiths? What was hers?

JS: Well, her mother kind of started her own faith. She didn’t go for any of the organized, but I think they started out in the Church of God. Her mother had a little group. Of course, I was a right hander.

BM: Your wife’s name was?

JS: Ruth Sara Smith.

BM: Describe her – you said she was the most beautiful thing you had ever seen. Describe her to me.

JS: Well she was gorgeous, I thought. She was really dedicated.

BM: When you went courting what sorts of things did you do? What would be a good date?

JS: We went to the movies and restaurants. She had never eaten a steak. It was mostly potatoes and gravy. So that was a big thing for her.

BM: What restaurant did you go to have that steak?

JS: There was a place right by Renton Junction, not far from where Long Acres was. There was a nice place back in the trees. I used to take her there. And we went to other ones, Seattle.

BM: So you got married what was the year you got married?

JS: We got married in Our Lady of Lourdes Church in South Park by Father Edmund Wilson. He understood the situation because he had become a priest from another religion. So he understood the situation and everything worked out good.

BM: Did you decide to start a family right away? You got married in 1942.

JS: Jane was born in 1948.

BM: So you got settled before you had babies.

JS: Well, I don’t think we made a decision, but it happened finally. It had to be Caesarean.

BM: Did she continue to work before you had children?

JS: She worked for a while, yes.

BM: You had a house. Were you living in South Park or Southern Heights?

JS: Before we got married, I had bought a home out in Kent. The apprentice before me was into race horses. We were friends and I went out to his place and I thought that was a great place out east of Kent. East Hill, they called it. So I bought a place there. I had a house and five acres. When we got married, I couldn’t get in because I couldn’t get the renters out of it. Finally they moved and so we got to move in to our house.

BM: That was a bit of a drive for you then to get into work.

JS: Not bad, about 10 miles. Down the Benson Highway and through Renton and over to Pacific Car.

BM: Your daughter said, “Make sure to ask him about different things.” So I want to make sure that I ask about everything. First, tell me a little bit about your daughters. They were born in ’48 and ’50. So you raised them in the Kent area, is that right? That’s where you raised your family, was over in Kent?

JS: Yes. Jane went to grade school in Kent. Kathleen went to school at St. Anthony’s school in Renton for a while. When they got older I was able to send them to Holy Names Academy. They both graduated from Holy Names Academy.

BM: Ok. Jane was born in 1948 and Kathleen, two years later in 1950.

JS: Yes.

BM: I understand you had some involvement with the Space Needle. What do you remember about the Seattle World’s Fair? Did you have any involvement in helping build the Space Needle?

JS: What I remember was our company built the Space Needle. One thing I really remember was our purchasing agent and I were sent down there to the Space Needle. Our company built the Space Needle but in a different location from Renton. They had a structural steel division at that time at First and Hudson. They built that Space Needle. The Space Needle has a revolving floor. They wanted to know if it would entail castings. Our sales manager and I went and they raised us up on the freight elevator, which had a plank platform underneath where the floor is now. They were getting ready to do the superstructure. Anyway, I determined that there was really nothing that was apropos to castings. So eventually they jobbed that out to Western Gear and they did the whole thing. That runs on tracks now.

BM: But you were up there way before —

JS: I didn’t like it either. [laughing]

BM: I can imagine! Did you have ropes that you attached and so on?

JS: Yes. But I didn’t get close to the edge. You run into those things. Anyway they went ahead and completed it. As you know the elevators are in the center. When you step out of the elevators you’re on a rotating floor which revolves once every hour.

BM: So then to transport the parts of the Space Needle to the Seattle Center grounds did you use trucks or did you use the train?

JS: Well, first they had to bend the steel. The man that did that was a real artist because those are big steel beams. Basically they come in a straight section. To put the beautiful curve it took a lot of heating and pressing, bending hydraulically. You keep bending it and heating it and bending it to get the beautiful curve. Otherwise it would look like a Tinker Toy.

BM: You were under a lot of pressure to get that building built in time. Can you talk a little bit about that?

JS: Yes. Actually, we didn’t have anything to do with it out in Renton. They had a structural division. When I started, the structural division was right in Renton. But then they bought out a plant at First and Hudson in Seattle. They used to machine the tank holds in there. There was like a tunnel and they bolt down 4 or 5 tank holds and they went back and forth on a track and the cutters stuck out from the side. Like a tunnel without a roof. So that’s where they bent the big beams for the Space Needle.

BM: Do you recall any other major projects that your company was involved in that you worked on?

JS: Well, we built the twin towers that they flew the airplanes into in New York.

BM: How did that project end up happening at your plant?

JS: They built that at structural division. They lost money on it because of the shipping. There were two choices. One by ship through the Panama Canal and the other by railroad. I forget which one caused the problem because when they got ready to start shipping the price had raised so much that Mr. Pigott decided to get out of the structural steel division at that point.

By that time they had bought out Kenworth. We bought them out in the ’40s. Kenworth was a two man operation on Lake Union. A guy named Kent and a guy named Worthington. Chuck Pigott had taken over the presidency of our plant and he could see the writing on the wall. So he knew that logging business was about over with. Now they’re the world’s largest truck manufacturer. They build Kenworths and Peterbilts. They just had a thing on TV, Ultimate Factories. They are building 100 Peterbilts a day. When I left the company, we were doing about 30 Kenworths a day. Kenworth was a separate entity over by Boeing Plant 2. That was a plant built by Ford when we were kids.

BM: You have some other papers there. I think you drew some other drawings. Is that right? Do you have some other things to share? Oh they’re some copies [of the map].

[Referring again to the map]

JS: What you have to remember about this, you have to imagine that you got off the streetcar here in South Park. When you walk out along this here there is a little blank sidewalk along here.

BM: Along the brick road of Des Moines Way.

JS: You were heading west and this is what you would see ahead of you. Ordinarily they put the North up here, but I thought maybe you were mainly interested in the Des Moines Highway.

BM: Yes, exactly.

JS: We would get off of the streetcar in South Park. We had a mile to walk to get home. We lived up here in Aline Heights.

BM: Thank you. I appreciate that. We’ll put that in the collections.

Please talk to me about how you got involved in hydroplane racing.

JS: I was fortunate enough to meet Ted Jones. Ted Jones designed the Slo-Mo 4. We became good friends because I had the patternmakers skill and the casting skill. Prior to that time they welded up the rudders and the engine mounts, struts, and all that stuff. Ted said to me, “John, I got to get you into hydroplanes.” So he drew me up one. I still have the drawings. I built one, it was called 135 cubic inch. When I got ready for the rudder and struts and everything, I could see that it would be a really great thing to cast. So I cast them. When he saw that, he thought they were the most beautiful things he ever saw. So that’s how I got into it. I did all the hardware for the Thriftways, the Budweiser, and a lot of the boats. Most of the boats across the United States.

BM: So this was after your official career, but sounds like a whole new —

JS: A whole new world for me. And a fun world because I got involved with the Budweiser and Bernie Little. Sold a few boats for them, and things. I met a lot of wonderful people. A different type of people, too. Whole different lingo and the whole thing. It was just a fun thing. Something I really didn’t ever intend to get into but I loved the boats because I thought they were gorgeous. I was more interested in the boats than the racing, actually.

BM: It sounds like that’s the subject for our next oral history when we get together next time.

JS: We built about half a dozen Thriftway boats for Associated Grocers. I did all their hardware.

BM: I bet they ended up winning a lot of trophies.

Well, Mr. Skube thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate it.

JS: Well, it’s been good. I enjoyed talking to you. I guess we covered quite a bit of ground.

BM: I think we did. It was our pleasure.