I’ve lived here for 86 years in this house next door. This area was called Riverton Heights. The original school, called Riverton Heights School was just off the Kelly Road at 138th Street. Kelly was the first pioneer up here in the town of Sunnydale. He blazed the trail up here. Most of the Kelly Road is abandoned now, however there is a section of it from 142nd to 144th still running. It ran from Robbins General Store to the town of Sunnydale. As new pioneers came out here the Kelly Road was pushed on all the way to Des Moines and Normandy Park and Miller’s Beach. Kelly’s Road would be from 142nd to 144th and then the Des Moines highway was built on top of Kelly’s Road.

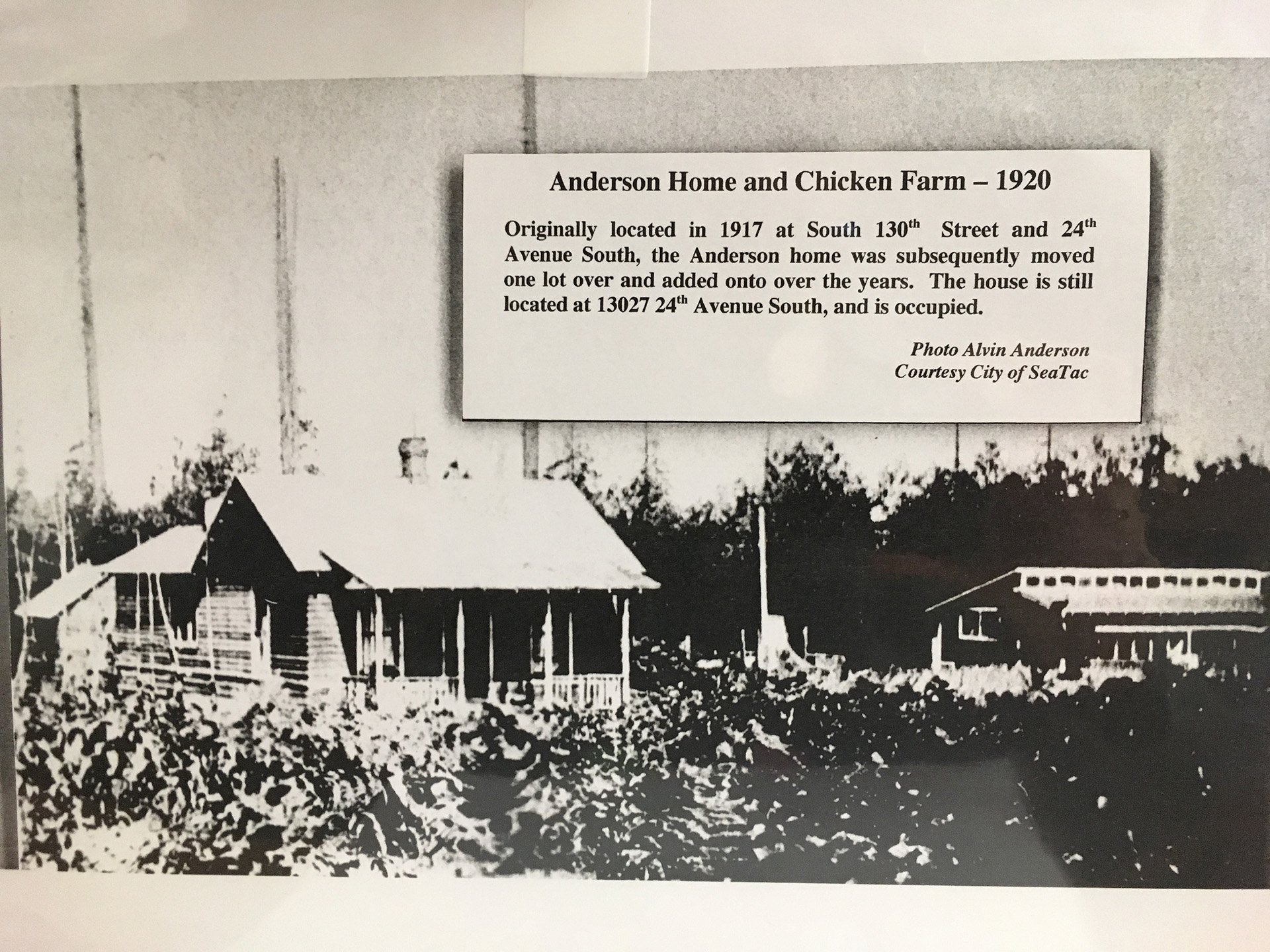

My father bought a piece of land out here. He emigrated from Sweden at the age of 19 along with his 16-year old sister. The two of them went to their aunt in Cleveland, Ohio. The 16-year old girl was able to get a job with a rich family, and there she learned to speak English. Then she met a man named Fred Anderson and they got married. My father worked for several years on the Great Lakes. After learning English and earning his first citizenship papers he decided to make a tour around the United States.

When he came to Seattle he found people from Scandinavia and an area much like the town where he came from in Sweden. He came from the middle part of Sweden, a little town named Djorbyn. When he got to Seattle he found all these people who were willing to help him. He found a fellow by the name of John Nordstrom. He had just been up in Alaska and made a little money in gold mining, so he came back to Seattle and opened a shoe shop. That became the basis for building the Nordstrom department stores.

To see that the young people did not get into trouble, they formed athletic and educational organizations and saw that they got jobs. There were three main jobs they could do here: work in the forests as a logger, work in the sawmills making lumber, or they could take the lumber and build a new town. My father chose to become a carpenter. From the time that he came here in about 1907 until forty years later he worked building the city of Seattle.

One day some Swede who had been here longer convinced my dad to take a ride on the Interurban. He was going to show him a house. He got out here on the Interurban from Occidental and Yesler Way. They came over a landfill. The tide flats had all been filled. Spokane Street had not been filled in yet so they came over a trestle there. They came out to the town of Georgetown. There the Interurban took down the trolley and got onto the line that had a third rail. From there all the way to Tacoma the line ran on the third rail.

But when they stopped at Riverton the boys got off and walked up the hill. On both sides of the street there were wooden sidewalks all the way up to 42nd Ave. At the section line the sidewalk stopped. From 42nd on up the hill the sidewalk stopped and they had to walk on dirt roads. Dirt roads were good for horses but they weren’t any good for automobiles. For automobiles they had to fill the holes with dirt and gravel. He came up here and they saw this house, just a small house out in the woods. It had been previously logged off.

In 1916 we used the Interurban to go to work and go to town. My Dad worked as a carpenter in town. He was making good money, $4 or $5 a day. Most people were working for maybe $2 or $3 a day. Later I think he made as much as $8 a day. Most of the people living around here were making much less. Anyway, he used the place up here for raising potatoes. My mother put in a vegetable garden and that kept them going in fresh vegetables for part of the year. Most of the year we relied on meat and potatoes. We bought flour by the sack and she made her own bread. We didn’t have grocery stores in those days Bread was too expensive. The living standard was much lower than it is today. We didn’t have the expenses that we have now. We had no electricity, so no light bill. There were none of these modern conveniences. But as I say, every year we were progressing. We lived better than other neighbors. We got electricity o the hill. Then came the radio, the automobile.

In 1916 we used the Interurban to go to work and go to town. My Dad worked as a carpenter in town. He was making good money, $4 or $5 a day. Most people were working for maybe $2 or $3 a day. Later I think he made as much as $8 a day. Most of the people living around here were making much less. Anyway, he used the place up here for raising potatoes. My mother put in a vegetable garden and that kept them going in fresh vegetables for part of the year. Most of the year we relied on meat and potatoes. We bought flour by the sack and she made her own bread. We didn’t have grocery stores in those days Bread was too expensive. The living standard was much lower than it is today. We didn’t have the expenses that we have now. We had no electricity, so no light bill. There were none of these modern conveniences. But as I say, every year we were progressing. We lived better than other neighbors. We got electricity o the hill. Then came the radio, the automobile.

Our food was prepared on a wood-burning kitchen range. That was our heat in the kitchen. Most people had only the kitchen stove. In the living room we also had a parlor stove. Most of the time we didn’t use it. We didn’t preserve much food except by canning. We did not raise our own meat. But we did try raising chickens, but we didn’t make much money at it. That was one of my chores too, to clean out the chicken house. We didn’t make butter. If people had a cow they would make butter. Duncanson had a big pasture out there, which is now part of SeaTac Park. Sunset playing field was his pasture.

In the 20s there was an ice man who came around to deliver ice, because we did not have a refrigerator. He didn’t have to knock on the door. We put a card I the window telling how many pounds we wanted; 20 pounds, 50 pounds or what ever you wanted. He’d walk right in the house into the kitchen, load it in the ice box and then walk out. Along about late in the thirties we started getting refrigeration. It was a progressive time of change. We had great change. When I was a kid we didn’t have electricity, no automobile, no radio, no television, no running water, no sewer. All these things came on one by one. Until about 1950 we had them all.

My mother had taken some courses and became a skilled seamstress. She didn’t work for anybody but she made our clothes. My uncle was working as a logger in the woods, making good money. So he would buy expensive silk shirts. After awhile he would give them to my mother. She remade them into shirts for me. So I went to school in silk shirts, and it caused fights too. One kid asked me where I got the silk shirt. When I told him my mother had made it he didn’t believe me, so that caused a fight. We had the good clothing, and always took off the good clothes after school, and put on old clothes.

Before school I would usually bring in a load of wood and probably the same thing after school. Later on I had to split the wood, and then later on I had to go out and cut the wood. One time I cut my thumb off and Dr. Nichols sewed it back on. He sewed my thumb on and then he also showed me how to split wood. We only had one doctor out here for years and years, Dr. Nichols. Dr. Nichols had two daughters, Bonnie and Winifred. I wonder whatever happened to them? He worked at the saw mill over there while he was going to medical school. He must have started in about 1912. He was the doctor out here until 1940. His office was in White Center but he lived down in Riverton. His house is still standing there.

When he got off the Interurban, after a day’s work, he got off at a little town there called Riverton. (There’s no town there now.) On the way home my dad would stop and get some meat for dinner. We had no refrigeration. The town of Riverton was at 42nd Avenue S. and 130th Street, right down by the river. The Interurban followed the river down through Kent and Auburn and then it cut through the hill and went through a tunnel and came out someplace near Fife, eventually went to Tacoma. It was sponsored by Stone and Webster, two engineering students who came out here at the turn of the century. They were MIT graduates who had a dream of connecting Vancouver BC and Portland, Oregon. They built the line from Tacoma to Seattle, they then built the line to Everett and eventually went up to Bellingham. But the automobile came in and made the Interurban obsolete. People would rather have their private cars.

The automobile was invented about 1887. Benz was the man’s name. He put a four-cycle gasoline engine on a buggy and he sold it. He made several of them that year and sold them too. Then he made more and he made improvements. He found that the engine had to be more powerful. If the engine was more powerful he had to find a way to cool it. So he cooled it with water and the water had to be cooled by a radiator. So that resulted in the radiator being in front followed by the engine followed by the driver. And behind the driver was a seat for the passenger and so the five-passenger car was developed.

About the turn of the century the automobile began to take shape. The powers-that-be realized that if the automobile got into the hands of the working man, if the working man could buy a car, then their (powers that be) way of life was in jeopardy. So they had to have some way that they could control the automobile so that it would be only for people of certain qualifications. Well, somebody by the name of Selden had taken out a patent on the gasoline engine. Anybody who drove a car had to pay royalties to the holders of the Selden patent. So the automobile was possible for only the privileged few. Henry Ford didn’t agree with that. He thought the auto should be for everybody. After years of litigation Ford finally broke the Selden patent in 1911. It took until 1920 until every family had a family car.

So when my father first came out here, it was many years before every family had a car. Des Moines Way was built in 1916. It was a brick road. The way from Seattle to Tacoma was by going by the valley highway through Renton, Kent, Auburn, Puyallup and so on. It was a long way around. Somebody thought of a short cut. They went up the brick road to Des Moines and then from DM by gravel road all the way to Tacoma. And that road took on the name of Highline Road.

When they were going to build a new high school here in 1923, there was a contest (I was in grade school at the time.) to find a name for the new high school. So they named it Highline High School, after that road. You can still follow that road to Tacoma.

My father came from Seattle to Riverton on the Interurban. From there on, he would walk. It was wooden sidewalk all the way to the Section line which was 42nd Avenue. That was the end of Riverton. Past that it was Riverton Heights, and we had to walk on gravel roads then, all the way up here.

He raised chickens, had a big chicken house. Somebody came around and picked up eggs twice a week, and we got a little money that way. Of course we got eggs for eating, and chickens. My father raised potatoes and my mother raised vegetables, and that’s how we lived. We raised a pig from time to time, but we never did learn to salt it to keep it. Some people could salt it, but we didn’t know how to do it. We had chickens and goats. My sister was sick with some digestive problem. They tried everything and finally landed on goats milk. Did I drink goats milk? No way.

This was not a Swedish community. My mother and father spoke Swedish to each other, but they always spoke English to me because I was going to live here the rest of my life and I had to learn English. It was that way with all of the others; the children did not speak Swedish, always English.

As a child I got up in the morning had to go to school when the school bell rang, went through my day’s schooling. I came home at night and had my chores to do. I had wood to chop and bring in, and a little work around the place. This was a stump ranch. My dad planted some potatoes, had a chicken house down there. The well, a hundred foot well, is here on this property. When I was ten I had a paper route, went to the pulmonary hospital which is now the Riverton hospital.

There were not many people around here. 24th Ave was “the end of civilization” so to speak. Anybody who lived on 24th or east of here could walk to the Interurban. Anybody who lived west of 24th, it was too far to walk. Everything south of 146th was wilderness. Very few people lived south of 146th. One fellow, named Evan Green, had a big chicken ranch at 160th and 24th South and that’s right in the middle of the airport now. Every time I go past that place I think that instead of chickens there are now big airplanes flying around there. Green owned the telephone company, and my dad wanted a telephone. When I was a little kid my dad and I walked up there to negotiate for a telephone. I was more interested in the railroad he had there between the chicken houses where he had cars that he could push around to take the chicken feed and manure around. Green was the owner of the first automobile around here. He was a big shot. He did not walk to the Interurban.

Once Henry Ford had broken the Selden patent, giving him permission to build as many cars as he wanted in any way he wanted to build them, and sell them to whomever he wanted, then Ford went ahead and by mass production was able to turn out these cars. They were not called Model T’s until after the Model A’s came out, then he referred to first ones as Model T’s. But we drove them all those years just calling them Fords.

They were different. They had a planetary transmission. All the other cars had a gearshift. The Model T had a transmission like the present automatic transmission. If you wanted to start the car you pushed the pedal down into low gear, let up the pedal and you’re in high gear. You had two speeds forward only. If you wanted to go in reverse you stepped on the reverse pedal. If you wanted to stop it you stepped on the brake pedal. The brake pedal was on the transmission, not on the wheels. There were four wheels, but no brakes. The only brake they had was on the transmission. It worked very well if you didn’t break a axle. If you broke an axle no way would you stop a Model T Ford. A lot of people were killed by that.

The Benz was a German car. He sold them, and each year he improved them. America had the merry Oldsmobile.

We lived at 130th and to go to school we had to walk to 138th and then up 138th. From there we had to walk up to the school. However, I didn’t go that way. There were skid roads in this whole region. They were used to skid the logs down to the river. With the help of oxen they had to drag all the timber over to the nearest river ad float the logs off to the sawmills in Seattle. One road was called the Mitchell logging road, now called the Military Road. The logs were skidded down to the White River. The rivers have now been diverted to prevent flooding. The water from the black River used to go into Lake Washington and over the locks in Ballard. The White and Green rivers were combined and the only thing that’s left now is the Green River. Before the rivers were diverted the whole valley down there would be flooded every winter.

The skid roads were all over this area’ there didn’t seem to be any fixed pattern to them. I assume the Mitchell Road was the main rod. There used to be a road here in front of us, from 128th to 146th, but it wasn’t much of a road. There was a skid road right here behind the house.

24th was the end of civilization. That was because of the herd law. East of 24th the herd law was in effect. If you had an animal, a cow or horse, you had to keep it in a pasture. West of this road you could just let the animal run loose. People had cows out here, and in the morning they’d turn the cow loose and it could forage for its food. There were no cars here at the time. In the evenings the cow was pretty sensible and it came back home to be milked and fed. In the morning she was milked and fed and then turned loose. We had several cows running loose here back of the house because there was no herd law. But right across the street, east of 24th, there was the herd law and you had to keep it in the pasture. There was a big piece of land here, the Montgomery’s farm, He had it all fenced in. He must have made money on his farm. I don’t know what he did; he didn’t have any milking cows, but whatever he did he must have made money. He took a trip to Jerusalem with his wife. They’re dead now.

There was a ten-acre farm across the street. He had a big barn back there and a big house.

I am the only pioneer left around here. There’s none as old as I am.

There were kids to play with at the school. We had a school up there. The Riverton Heights School (old one) was a two story building, two rooms down and two rooms up. When I went to school, of those four rooms only two were occupied. We had no electricity, no plumbing, no sewer system. We had two outhouses out in the back and that was it. In a few years my dad and a few other people got together and donated $10 or so apiece and they got the poles set from 24th down to Riverton. They had electricity down there because the Interurban ran on electricity. So of course Riverton had electricity and we just tapped into it. Puget Sound Power and Light did it. We paid for the poles and they came out and set them, so we got electricity up on 24th Avenue. And some of it ran down to the school. Once we got electricity at the school, we could put in a pumping system to get water out of the well. Then they could put a plumbing system in with a lavatory and a modern flush toilet.

We kids had some chores to do. I cleaned out the chicken once in a while. We had about 150 chickens. We kids played games like Pump, Pump Pull Away, Dare Base, Annie I Over. We had no formal games of basketball or football, but there was baseball. The big boys did. The schoolyard was very small. It’s still in existence. The Christian Life School is in there now. The original school burned down but fortunately the school bell was saved, and the city of SeaTac has it up there now in front of their community center.

The school was the only organization I the community. They probably had a PTA. The only entertainment we had were some events at the school. But, as I say, there was no electricity for many years. Wall lamps or kerosene lamps were hung on the side. They weren’t very safe. We had Christmas trees with candles on them too. Sometimes the tree caught fire and many houses burned down. We had no fire department for many years. If a house caught fire, it was down; there was no way of putting it out.

I went to Riverton School. When I was about in the third grade or fourth grade, in 1921 or 22, they formed school district Union District R. That name was applied to it. There were eight districts (individual schools) combined into that Union (Highline) district. Highline High School was probably started I 1921 and the first class was in 1922.

We had a class of seven or eight people in the seventh grade. Then in the eighth grade we went to Highline with kids from all the other schools. We had to take state examinations. The teachers had a syllabus for what they were going to teach. Now they do it backwards. The kids are being tested on something they haven’t been taught.

I went to school with Tom Hulse and Gummie Huhn. Tom went to Ellensburg the last two years. The professors were jumping all over him. They said, “You know you’re going to get a job (Hulse’s father was the Superintendent of Schools). You’re not studying. You’re just sitting there.” He knew he already had a job in Lake Burien School. I was in his classes.

When I got through with high school, it was almost automatic that I went to work for Mr. Koberbig, superintendent of Fisher Body. We made wooden automobiles for General Motors cars. We naturally went down there and got a job right out of high school; many of us did. It was very dangerous. People would stick their fingers in the machinery ad get them cut off. Joe Klatch cut all the fingers off his right hand. When I went there they didn’t put me in a job anywhere near the machinery. They put me in the glue room. I was gluing up the parts. We made the complete frame of the automobile. It was covered with tin. They made them in the building, which is still there, where the Kenworth trucks are built now. We made the wooden autos. Both Ford and Chrysler were making steel bodies, and advertising how superior they were to the wooden bodies. General Motors advertised how superior their wooden bodies were.

One day Fred Taylor, who was a quarterback at Highline High School when we went there, made a proposition to me. He said, “Let’s go over to Ellensburg where we can play football.” I had worked at Fisher for about three years, and I said, “No, I don’t want to go to a girl’s school, a Normal School.” Well, anyway, he talked me into it and we went over to the Normal School and played football for four years. Fred and I played for three years and eventually Gummie Huhn and Tom Hulse, Norman McLeod and several others came over. And they became teachers in the Highline District. Some of the buildings there now are named for the teachers I had. In those days it was just a glorified high school. I didn’t learn anything. As far as education courses are concerned, they were a waste of time. When it was becoming a college they began to teach math and science and that was my long suit. I took all the sciences, chemistry and physics, and all the math they had. I taught in the Highline District for 35 years. I was at Lake Burien, Puget Sound (one of the best buildings they ever built, and now they’ve torn it down.) and when they built Evergreen I went there and became the head of the math department. I did not coach football, I only taught.

Our family did not play games or cards. By the time my father got home from work and walked up the hill from the Interurban he was too tired. Eventually he got the Model T and drove to work, but he was tired after a day’s work. We didn’t have any games to play anyway. But I remember one day I came home from school, the third grade, and said that my teacher had told me that we could hear music coming out here from Seattle – on the new invention called the radio. I told my dad that sh had heard music coming through the air and she could pick it up on this radio. My dad said, “No, it can’t be done.” Anyway, about that time one of his young friends from Sweden came over here and worked and began buying the parts and assembling a radio. He told my dad he would build him one if Dad bought the parts. So my dad bought the parts and so we had a radio before they were sold I the stores. It had an A battery (a bi storage battery) that lit the tubes up, and a B battery, a big dry cell, and then a smaller cell called the C battery. That wa a great invention, that radio. You can get one at 130th just off East Marginal Way in Riverton, a store right nest to the barber shop. It was a 201=A radio (not a crystal set).

As kids we used to make a crystal set by taking one of those round salt cartons and wind the wire around that and then put the crystal set in there and it would play.

I had cats when I was a kid. When I was older my mother got a dog. After my mother died and my dad remarried, but he kept the dog for many years.

During Prohibition people would go to the Studebaker Dance Hall at 128th and Des Moines Way. Near there was a trail they called the Snake Trail. After the dance people would drive their cars up there and drink whiskey. No, they didn’t have stills. It was Canadian stuff, in regular liquor bottles, not homemade still stuff bottled in fruit jars. When I worked at Fisher Body I knew one of the workers down there that was selling it on the sly. I don’t know of any stills out here. I heard (after he was dead) about one fellow who had a still out here somewhere, but the still exploded, burned the building down and burned him to death.

My Mother took care of all the groceries. Before we had the automobile she baked her own bread, preserved her own fruit and vegetables. My dad raised the potatoes. Most of our meals during the winter consisted of meat, potatoes and gravy. During the growing season we had carrots ad corn grown by my mother. We had a well. Monday was wash day with tubs and a washboard, no machine. My mother washed clothes by hand. We didn’t have a washing machine. Some people had a washing machine, very old style. It was a progressive thing. Later on we got an electric washing machine, and now we have the automatic machine. She had a boiler to heat the water, hung the clothes out on the line to dry. Tuesday was ironing day. Then one of the days was for baking bread. Toward the end of the week she might go to town on Friday or Saturday, but very seldom. We did not make soap. Maybe the Kelly family in the 1880s did that.

We used to walk down to the Interurban to ride to town, and then my dad would pick us up to go home. My earliest memory of transportation was walking down to the river, to catch the Interurban. There was a boy near the tracks that would pull down the flag, the signal. We had to pull down the handle and the local would stop and pick us up. Riverton was a station. It had a wooden building. Some others only had a bench by the side of the road. The Limited would go at 65 miles an hour. It did not stop at Riverton. There is a story about that. There was a girl with an umbrella who stepped out on the tracks to get the local, but the Limited came along, did not stop, and she got killed. That story has been written up in the History of Tukwila by a professional historian. I think there was only one track.

I remember downtown Seattle without so many people and cars. Before we had our automobile there were not many cars downtown. It took abut ten years for every home to get an automobile. By 1920 every home had a family car. You see, in 1911 Henry Ford broke the Selden patent, which allowed him then to build his cars.

I lived on 16th Ave and 144th for awhile. I taught at Evergreen from the time it opened until I retired in 1974. I opened Puget Sound Jr. High too. It was a mistake to abandon Puget Sound. Carl Jensen had the idea that we were going to be modern with campus type schools. Those schools got mold. Highline High School is a wood frame building with brick veneer. PS was reinforced concrete, a good heating system, oak floors on top of concrete. At Evergreen they started out with seventh grade and went through twelfth. They built Cascade Jr. High after that.

During World War II, I was teaching school. One day I had to go down for an exam but they sent me a letter saying I was exempt. They wanted to keep us in the schools to take care of the kids. So I got exempted time after time. I don’t think any of our teachers got drafted. Except Dimmit’s son, he got killed in the war. I the Highline High School there were many Japanese people, ad they were taken to internment camps, some went into the army eventually.

There’s not much to tell about the times when I was teaching school. When you talk to Gummie Huhn he’ll tell you about those times. He was in the front office of the superintendent. He worked on attendance or something. Tell him that you talked to me.

I knew the kids that used to run around together with Tom Hulse and Gummie, and I know who invented the transmission. The automakers were interested in the transmission, but they would not buy it. They were going to produce the Dynaflow or something, but his was a different kind of operation. He had a system byy which it shifted automatically.

I remember when Tom Hulse was almost killed in a bad accident. The boys were driving down the hill from White Center down the Boeing hill. So he lost a year of school. Tom has passed away, but Gummie is still with us. He seems to be pretty busy, too busy to be interviewed.

Dick Dunbar went to Highline High School also. I know who he is, he has worked with the SeaTac people on their historical society. He has made copies of some of my pictures. Tell him to come out and take another look at some more of my pictures.

So, Gummie is doing all right. I’m not doing all right. I’ve got a bad heart and some other things wrong with me. I’m 86, next month I’ll be 87.